Jon Hamm: The Best Life Interview

Jon Hamm, star of TV's Mad Men, reveals the secrets of manliness in a postmodern world.

I am hoping Jon Hamm will be wearing a concert T-shirt, reading a comic book, or eating a cupcake.

Maybe in person he'll be a little nervous about being interviewed for the cover story of a national magazine, emitting a Beavis laugh at everything he says. I sincerely hope that he'll be nothing like the Brylcreemed, three-piece suited, silent, confident character he plays on Mad Men–not only because I have no idea what to say to that guy, but also because that kind of guy makes me feel bad about myself. Every time I watch the show and see him playing Don Draper, quietly bossing around the other people at his 1960s New York advertising firm, I look at my T-shirted, cupcake-eating self and wonder how confused Darwin would be to see how man devolved so quickly in half a century.

So I am none too happy when Hamm suggests we meet at the driving range. The driving range? Is the bull-fighting stadium closed for the day? Worse yet, despite how conspicuously chiseled-handsome Hamm is, did he need to pick the one place where he'd be camouflaged by other rich-looking athletic white guys?

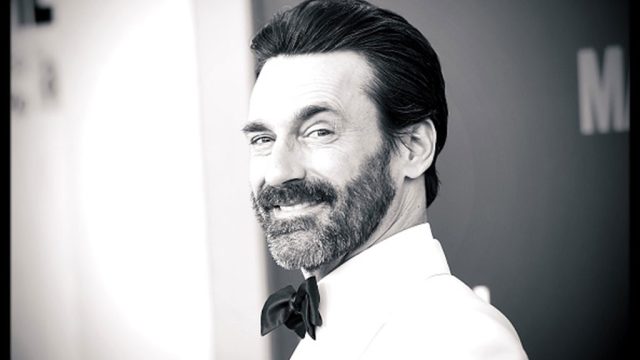

But there he is in front of me, 6-foot-2 in Levis, a polo shirt, a St. Louis Blues hat, and perfect stubble, thwacking dead, public-park driving-range balls 200 yards with a three wood. This is going to be a long day.

The meeting progresses just as expected, with me playing the hapless slacker and Hamm fixing my stance and teaching me to keep my eye on the back of the ball, which actually allows me to hit the thing pretty well. He was taught by his grandfather in Ste. Genevieve, Missouri, a tiny town on the Mississippi, about an hour south of St. Louis. His grandfather also taught him, of course, to fish and hunt. "I like shooting guns, but killing shit wasn't for me," he says. "Seeing a deer get trussed from the rafters of a garage was a little visceral, to say the least."

Seeing my struggles with the golf balls, Hamm suggests we bail on the golf and go to the tennis courts, since that's a sport I at least know how to play. I won't belabor the match, which sounds a lot better than it was at 6 to 3 (my three wins are due to a shocking amount of double faults and unforced errors that I attribute to the pressure of my occasionally pretending to write cruel observations in my notebook). Hamm does, however, get a little bit of a workout, so afterward, we go to lunch at the Mustard Seed Café, a lunch spot whose sidewalk tables he frequents regularly with his Shepard-mix mutt. Inside, we find his tall, blond girlfriend, Jennifer Westfeldt, finishing a salad and working on a script (she is an actress-writer-producer). As soon as Hamm introduces us, I lie and tell her I kicked his ass at tennis. She looks confused, like I must have misspoken, and then takes another look at me and goes from confused to horrified, as if she might end their 10-year relationship right there at lunch. I confess the truth and her brow smoothes out.

Hamm and I leave her to get our own table, and he orders–classic man-style–a BLT and potato salad before railing like a sensible Midwesterner about other L.A. restaurants. "I went to a place that had an $18 omelet," he says. "Come on. An $18 omelet? I remember going out in St. Louis and thinking I'd get in trouble if I ordered the thing that costs double digits."

I find out Hamm plays poker regularly and never goes to the gym, preferring to play baseball or other competitive sports, and am braced for a litany of other man pursuits. But instead, he starts talking about video games. "Growing up, the bowling alley had a pretty sick arcade," he says. "I was a Donkey Kong guy, big time. But I'd play anything. I still go. If I walk by an arcade, I'll walk in just to see what's new." He's telling me about his favorite Atari games (The Activision Decathlon, Pitfall) and his first computers (TI-99, Apple IIC), and I'm thinking, This guy isn't all that whiskey jock after all. Better yet, when he explains that the reason men looked better in the Mad Men era is that they dressed up, combed their hair, and tucked in their shirts, and I ask him if the show has improved his wardrobe, he says no. "It's the f–king 21st century," he says. "I'm comfortable." And, watching him pour two entire sugars into his Arnold Palmer, I'm incredibly relieved to know that, at 37, unmarried with no kids, he is the same kind of rejuvenile as every guy I know.

Right then, a woman in her sixties gets up from her lunch with a friend at the next table and walks over. Her cell phone is out, opened to camera mode, and I think, She is not the Mad Men demo. But it turns out she has no idea who Jon Hamm is.

"Can you help me find the photos to look at?" she asks, handing him the phone. And he takes it, no greeting taken or offered, so I figure he knows her.

"My stuff. Let's look in there," says Hamm, punching buttons.

"Uh-huh."

"There. Pictures."

She shakes her head in self-disapproval. "I've been trying to do this all day."

"My thumbs are too big," he says, smiling. "Ah. There's your pooch."

"Thank you so much."

As she leaves, still without introducing herself, contentedly heading off to show photos of her dog to her friend, I realize that Hamm is the man I feared from the get-go; it's just that the definition of being a man has changed from 1960. The guy just did the modern equivalent of helping a little old lady carry groceries to her car. Everything about him is a modern interpretation of adult. He may not be married, but he lives with his girlfriend of 10 years. He is politically progressive, but for him, it's about responsibility. "I'm for raising taxes. I like nice flat roads and schools you can send your kids to. I don't mind paying my share and someone else's share," he says.

It's that part of Hamm that he's able to translate into Don Draper, the Mad Men character he won a Golden Globe for in his first season, beating out Hugh Laurie and Bill Paxton. It's the quality that Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner, who wrote for The Sopranos, was looking for when, in the pilot script, he described Draper as a James Garner type. "Jon has an old-fashioned leading-man quality," says Weiner. "They're really out of style. Now he's the bad guy or the doofus or the other man. Because in a movie like Knocked Up, the witty chubby stoner guy is the leading man. Jon isn't snotty or childish. He's an adult. He has a lot of Gregory Peck in him."

Hamm has been an adult for a long time, maybe not since his parents divorced when he was 2, and maybe not even after his mom died suddenly of cancer when he was 10 and he went to live with his dad and his grandmother, but probably since he was 20 and they died too, and he became one of those kids who spend college breaks and summers living with a series of friends' families.

The weird thing is the kind of people he met there in St. Louis, through those families: They're people you've heard of. Some of this can be explained by the fact that Hamm's dad was pretty successful, and some can be explained by the fact that Hamm's mom left him money to go to a really good, progressive private school. But most of it can be explained by the fact that Hamm has that quiet, athletic, good-looking confidence, and it draws other confident people to him.

In fact, Hamm's ability to attract famous people is Forrest Gumpian. His high school girlfriend, Sarah Clarke, whose family he remains close with today, later played the villain on the first season of 24. And he lived with the family of Mary Ann Simmons, whose husband, Ted, played for the Cardinals. He's still really close with the Simmons's son Jon, who was coming to stay with him the day after our tennis outing. And Hamm didn't make these friends through loyalty. When Simmons went to the Brewers and played against the Cardinals in the 1982 World Series, Hamm rooted against him. "Nothing personal," says Hamm, "but, dude, it's the Cardinals."

"He was the cool guy in high school," says Joe Buck, the baseball sportscaster. "He was the cool guy in college. He's not the before-and-after pictures where he was the nerd in high school with tape on his glasses. He was always the guy you noticed." Buck, a couple of years older, got to know Hamm through Sarah Clarke's brother, Preston. And Preston introduced Hamm to his college buddies, including Paul Rudd, who helped Hamm find a manager when he arrived in Los Angeles.

"I found him to be somewhat intimidating," says Rudd. "I played Trivial Pursuit with him, and he was a senior in high school and I was a freshman in college, and he went straight for yellow. He wanted history questions. If going to yellow in Trivial Pursuit is your first choice, impressive. And how not Jewish is Jon Hamm? But Jon Hamm can throw out a kugel joke and do it the right way. Smart, handsome, and athletic. But he's also very funny. Guys like that are usually not funny."

In fact, Hamm filled in as the host of E!'s reality-show roundup, Talk Soup. He got the job when Joe Buck bailed on the gig at the last second after reading the snark-filled script left under his hotel room door and panicking that it would interfere with his sportcasting gravitas. He quickly suggested Hamm.

But Hamm is also somehow friends with Jimmy Kimmel and got tight with the members of the band Rilo Kiley when he met bass player Pierre de Reeder through another friend. And remember, until Mad Men, the 37-year-old was more a waiter than a successful actor. "He knows every single place in town, but doesn't go out a lot," says January Jones, who plays his wife on Mad Men. "He knows the jazz bars. He'll go to Jeffrey Katzenberg's Oscar party and know all the people in the room. I'm like, 'How do you know all these people? I've been here a long time too, and I'm freaking clueless.' He's a good talker. He works a room, that guy. He's like a politician."

All those skills might help him now, but until this job, Hamm struggled. Unlike George Clooney, who started cute on The Facts of Life and manned up later, Jon Hamm has always looked older than he is. When Hamm drove from St. Louis to Los Angeles in 1995, with only $150 he had saved after a year of interning in the drama department of his old high school (like some superhandsome version of Welcome Back, Kotter where the teen boys hated him), he couldn't get auditions. All the other 25-year-olds were playing teenagers on Dawson's Creek–type shows. He lost his car when, after $1,600 in parking tickets, the city decided he'd be better off without it.

He met Westfeldt at a friend's party, and she thought he was an arrogant prick. But when she needed to cast an unpaid part in her off-off-Broadway play, and that part was kind of arrogant pricky, she auditioned him over the phone. Hamm was working as a set dresser for a soft-core porn film. "A friend of mine from college–a girl–couldn't take working on the creepazoid downtown toxic set anymore," he says. "It seemed like a wonderful way to spend 12 hours a day five days a week for $150 a day…nonunion, no benefits, just a shitty job with a lot of boobs and sad people. Hollywood, baby! Suffice to say, when Jen called with an actual acting opportunity, my days as a set dresser–all told, about a month–were over."

Hamm called a friend in New York and asked if he could sleep on his couch for six months. The play, which later turned into the 2001 movie Kissing Jessica Stein, started Hamm's and Westfeldt's relationship. Around the time they shot the movie, Hamm finally quit waiting tables, thanks to a recurring role on The Division and then Providence, which are both shows for women. He played a fireman and then a cop and, I'm assuming, acted sensitive and not at all Don Draper-y. When Providence ended, he kept getting close to landing TV jobs–seven network tests in which the part had been whittled down to a few actors–but other than a role in the movie We Were Soldiers, he was back to not working. "When you're on a show and going to work every day, and then it is taken away, it gets hard," he says.

Mad Men didn't seem to be the kind of vehicle that could propel Hamm into the higher realms of Hollywood casting (he is now getting movie roles such as this winter's remake of The Day the Earth Stood Still, with Keanu Reeves). When Mad Men was launched, AMC–the old-movie channel that is constantly on at your dad's house when nothing is on Fox News or the History Channel–had never made a scripted one-hour drama series. Even if it was good and was marketed well, it's tough to get people to try out a serious period drama without cops, lawyers, doctors, or the mafia. Worse, the main character is an antihero who's short on likability: He's coming up with cigarette ads after looking at studies that link cigarettes to cancer, cheating on his wife, and saying things to his mistress like, "What you call love was invented by guys like me to sell nylons." And even though critics and Golden Globe voters love it, ratings have not been all that high.

"Any success I have has not been a steep ramp," he says. "I've been doing this for a long time. But it's an adult show. It's not Hannah Montana or Indiana Jones. It's this interesting thought piece that strikes a chord with a particular segment of our culture."

Hamm sells his character Don Draper with his smile. It's a smile that hides more than it reveals, which works well since he has been lying about everything: his real name, his background, his two mistresses. Wayne Salomon, Hamm's high school drama teacher, recalls that, of all the gifts Hamm has as an actor, his smile was the most fun to work with. "He doesn't have a glamour-boy smile," says Salomon. "It's a quirky smile. It communicates something you'd like to know that he's not telling you. That's his cool. He seems to have a greater knowledge than anyone else does."

Draper, though, doesn't have that knowledge. Just as Faulkner's novels are about the confusion and sadness of Southern aristocracy watching its corroded empire crumble, Mad Men is about white men becoming aware that the patriarchal era is crumbling. Draper has slightly more awareness of this than do the other men in his advertising firm, which only makes him less happy. It looks, unlike everything I'd ever thought about the pre-Vietnam era, like a much harder time to be a man.

"That's what our show is about," he says. "They were full of shit. They didn't know what they were doing. It makes you look at what that definition of 'being a man' really means and is there a happy medium. Instead of subscribing to this definition of a man or dude or guy, do what you want to do, buy a f–king yellow Mini Cooper. Get over it. It's a f–king fun car to drive. You can do all the other man stuff and be unsatisfied."

It isn't until right then, to be honest, that I understand what everyone likes about Hamm, why he isn't the bad guy or the doofus that guys like me are supposed to beat out for the girl in this age of geek chic. He's a more complicated hero, the high school quarterback who gets the other jocks to leave the nerd alone. He's old-school not because he's secure about who he is, but because he makes other people feel secure about themselves.

On the way home, for maybe the first time in my three and a half years since buying it, I take down the top, gun it through some turns, and feel totally confident driving my f–king yellow Mini Cooper.

Originally ran in Best Life September 2008